[This is the first of a three part series about a recent journey. Parts two and three will come out next week and the week after. French words are italicized; some, not all, are translated.]

PART I. HOME GROUND.

The Shape Of A Short Trip.

Inspiration to explore my neighborhood came from writer Paul Theroux. I first heard of this author when I took a train from El Paso in Texas to Mexico City with a backpack, decades ago. I paid 36 dollars for a 36-hour train ride in an old 1940’s American train caboose with my own cabin, including toilet and bed. A conductor walked along the hallway swinging a silver pail and selling iced beers. The train sometimes stopped in the middle of nowhere and we’d step outside and buy homemade tamales from kids.

During this trip I met a house painter from the highlands of Colorado. He suggested reading The Old Patagonian Express—By Train Through the Americas by Theroux. I did. Years later, the author’s writing inspired me to join the Peace Corps. I ended up in the same African country where he served—Malawi—and on the same month that we volunteers arrived an article appeared in National Geographic, written by Theroux, about his revisit to that nation. This curiously timely coincidence encouraged me to continue wandering. I savored his book Riding the Iron Rooster—By Train Through China while malaria ridden in a village without electricity or running water south of Chitipa in rural Malawi, and years later while working in the desert outback of Namibia, Africa, relished The Happy Isles of Oceania.

Theroux’s latest travel collection is Figures In A Landscape—People & Places. I read it weeks ago. In one essay he mentioned a desire to explore his neighborhood and I was seized with the sudden certainty to do alike.

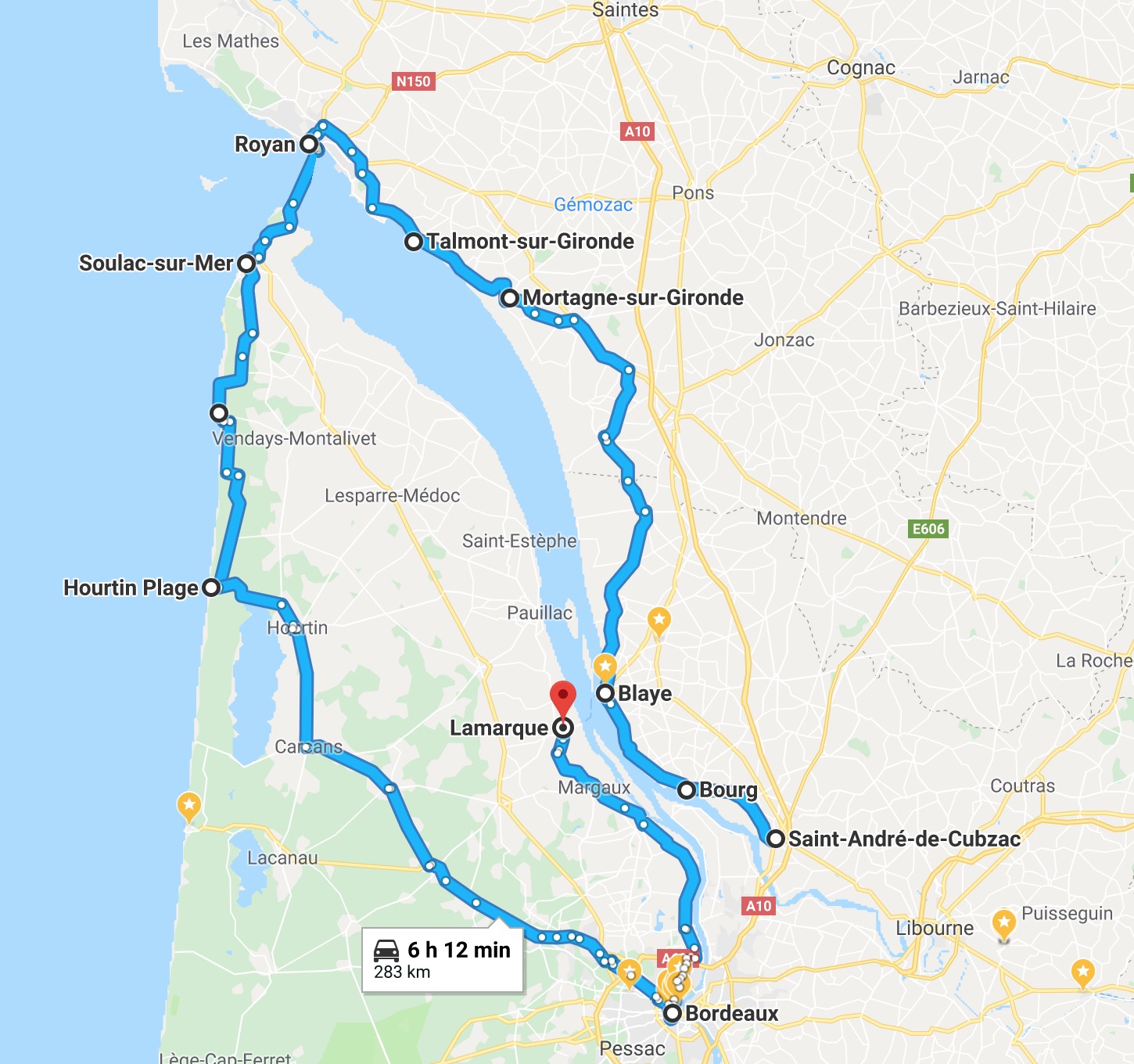

How to explore my neighborhood here in southwest France? First, my vintage, bulletproof Mercedes that once belonged to the Nigerian ambassador in London now lacks air conditioning and the motor is prone to overheating. This means I can’t travel too far during any brutal August day because the heat—la chaleur—will be sweltering and may cause engine problems. Yet I had to get beyond known terrain. Before plotting a route on Google maps I did so mentally. Locations to visit unfurled like a counterclockwise semi-spiral across the provinces of Charente-Maritime and Gironde. The trail resembled a snail’s curl, or the cross section of a squashed croissant. When I looked at a map this little route was not a spiral so much as a reverse P, or a capital Q. Finally, I plotted this tour on Google and the shape of the journey resembled a tilted slipper, or an amoeba with a flagella tail. Perhaps a partially peeled banana. In some regards, then—yes—a spiral.

But, seriously, who cares?

I stuffed a sweater and corkscrew and extra iPhone batteries into a cotton shoulder bag and throttled off at dawn, beginning the wonky semi-spiral path leading, of course, back home in time for weekend parties. The route began at Saint-André-de-Cubzac, headed north through hometown of Blaye, upward to coastal Royan, across water by ferry to the Médoc, southward past beaches and then on to Bordeaux city.

On y va. Let’s go!

Saint André-de-Cubzac, Bourg, Corniche de La Gironde

I entered Saint-André-de-Cubzac at a traffic roundabout with a statue of a leaping dolphin wearing an angled red cap, because this is the birthplace of ocean explorer Jacques Cousteau. I then slipped into a parking space outside the gare—train station—and wandered off to hunt for the morning market.

Linked to a major motorway as well as a railway line, and located on the Dordogne River, Saint-André is a gateway to greater Bordeaux city. This town has long been a center of commerce. Twelfth century rulers built north-south and east-west roads (known as the ‘cardo’ and ‘decumanus’–terms invented by clever Tuscan Etruscans) with a church at the intersection. It was pivotal for trading wine with those living in that angle of land between the Dordogne and Garonne rivers known as ‘Between the Rivers’ or ‘Entre-deux-Mers.’

Streets here hum and moan and screech with traffic—chortling semi trucks and belching SUV’s. These pass handsome buildings assembled from tan sandstone. Many rues include clusters of hairdressers, banks and real estate agents.

I passed a jogging girl and a man painting the iron rails around his garden. An ambulance driver honked at his friends. But where was the market? Better still, where could I get a mug of coffee? I walked past the stone Justice de Paix building where a woman dressed in orange pulled her matching brick colored shopping trolley, obviously heading to (or from?) some market. I followed.

Streams of strollers coalesced near Place Raoul Larche, where I entered Bar Brasserie of Cafe de l’Hotel de Ville across from a charcuterie. There I ordered a grand cafe crème from a stout, affable tanned man who, when I asked est-ce que c’est un marché aujourd-hui? nodded and replied simply, oui, then pointed in the direction from where I just came.

Merde. Which means, shite. Had I somehow missed the market?

I sat and sipped the bitter morning brew on an unkempt terrace littered with ciggie butts. Knolls of grass poked through cracked masonry where roots, long ago, heaved through bricks.

Yet, aha! There was another road leading slightly uphill and to the left. I finished the coffee and moved that way past Le Rolling Snack, the Boucherie Fortin (‘entrecôte bordelaise Euros 1.90/kg’) and found a sign: Marché Réglementé (regulated market) outside a parking lot where stalls covered in white canopies stood.

Although not as picturesque as a market in, say Sarlat-la-Canéda or Périgueux in the Dordogne, the wares were fresh and the sellers flashed friendly smiles. There were covered stalls and portable refrigerated counters and food for sale included massive green grapes, fig jam, sweating watermelons and Madagascar crevettes (shrimp). There were sesame loaves, firm ‘haricot’ beans and skinned rabbits – heads and bulging black eyeballs still attached. A uniformed pair of Police Rurale officers patrolled, and the sun began baking shoppers by 10 a.m. I heard the scoop of ice and vendors whistling and the eternal trio of farewells, spoken together: ‘merci, bon journée, au revoir.’ I bought a loaf of pan muesli from a smiling dark haired beauty with turquoise painted fingernails.

This market square—a parking lot that sometimes transforms to a social quadrangle—is bordered on three sides by flourishing trees and on a fourth by a community center. It provides a lively gathering point for neighbors and shoppers inspecting colors and shapes and textures of unpackaged wares. Here, twice weekly, locals bond with market vendors under the lash or scorch of outdoor weather. These open-air markets excel not just as shopping venues but as places to share news with neighbors and even, for a stranger such as myself, making me feel suddenly welcome.

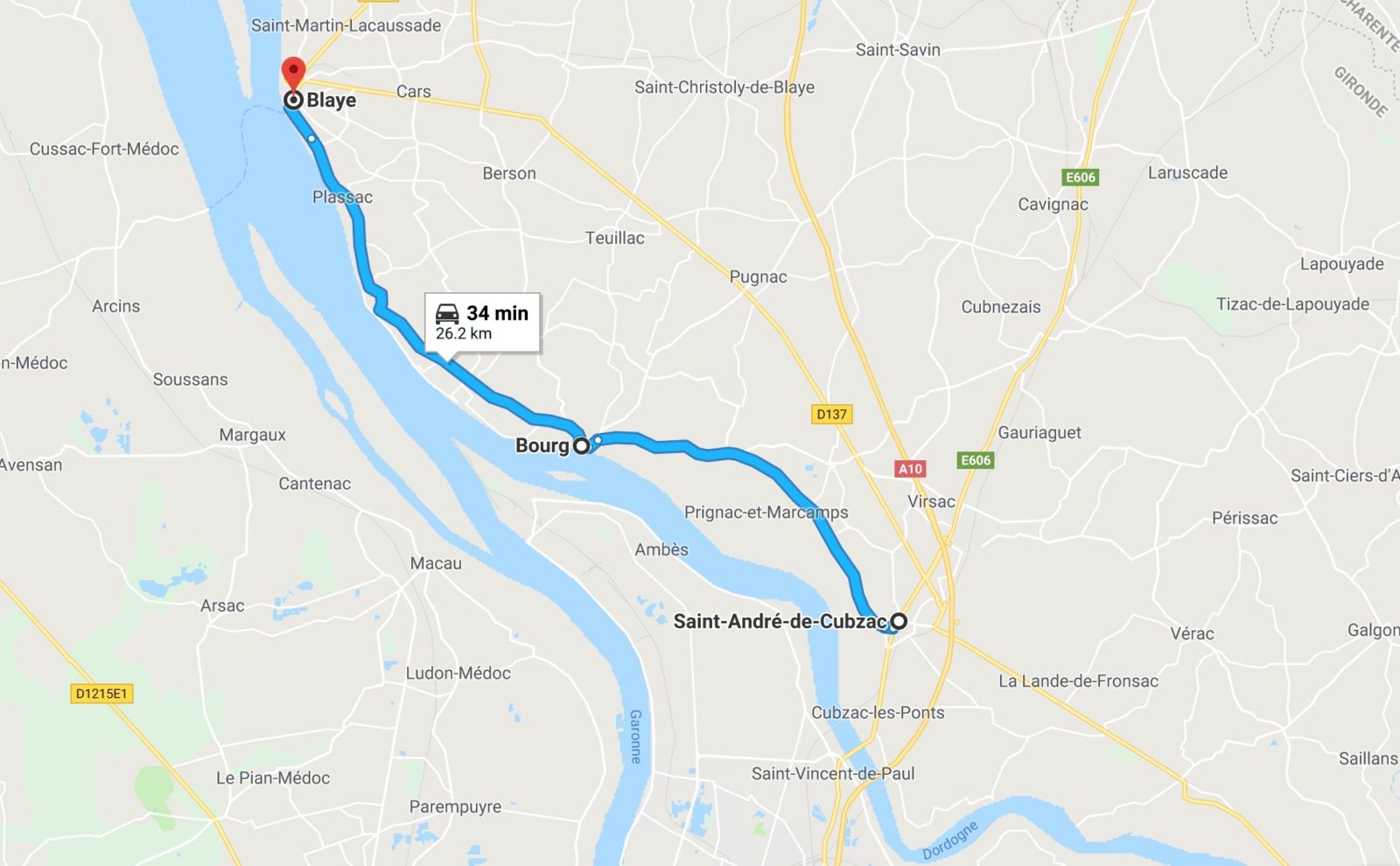

I returned to the car via back alleys, then drove north through Saint Gervais past the twin stone round towers outside Château de la Brunette. This road passing vineyards, la route du vin de Blaye et Bourg, wends over speed bumps through the town of Prignac-et-Marcamps, where a side road leads to Grotte de Pair-non-Pair. I had visited that site before: a 65-foot long cave where generations of Neanderthals and (later) Cro-Magnon humans lived. Protected from weather, wolves and bears, generations lived here until some 20,000 years ago and carved images of mammoths, rhinos and giant deer on walls.

Bourg

Then into Bourg, a special place not only because of wines (think Châteaux Gros Moulin, Mercier and De La Graves) but also because the curling blacktop road down Rue des Douves leads to an ancient port on the Dordogne River, once a keystone for Roman and medieval commerce. The city is also called Bourg-sur-Gironde, although this is technically incorrect because it sits along the Dordogne River, and not the Gironde estuary. Hundreds of years ago, before the estuary silted up and moved the confluence of the Dordogne and Garonne rivers four miles (6.5 kilometers) upstream and north, Bourg was on the Gironde. That’s why it was built as a fortification, in order to view and defend the entire estuary. No longer. You can call it Bourg-de-Gironde (‘de’ instead of ‘sur’) because it belongs within the administrative department that also happens to be named Gironde, but locals might not warm to that. Save yourself a hassle if you visit and just say Bourg.

This city was once, centuries ago, a stopover on the timber route, when inland and upriver trees from the forests of Cantal—between Bordeaux and Lyon—were shipped downriver for making leather or barrels or the supports for coal mines in boats called gabares. After delivering their wares, these boats were axed up as firewood or fencing and the pilots jogged back upstream to their homes to repeat the process. The Dordogne River was only navigable for a few weeks each year, and during then hundreds of boats floated downstream to deliver their sellable goods.

Today Bourg is quiet and peaceful and soaked with history, whether of medieval carpenters building catapults for castle invasions or of passing boats with quarried sandstone moving from Saint-Émilion to Bordeaux to provide construction materials for that city’s cathedrals and châteaux.

The town includes a covered structure that was was 18th century water pool, a communal laundry point. There is also a beautiful arch, made both from natural limestone and masonry that covers a sloping pedestrian walkway. From the upper ramparts (below tree cover and the shadow of a church spire) is a strategic view of the great, glissading, often log-bloated waters of the Dordogne River miles south of where it merges with the Garonne.

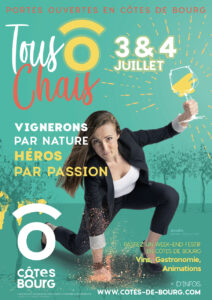

You stop in Bourg. You don’t stay in Bourg. Beside the attractive port and lovely ivy and flower coated walls there’s little to do except visit the glass walled wine bar—Maison du Vin—when it’s open on Fridays and Saturdays in summer, or the annual Nuit de Terroir food, drink and music festival organized each August by the region’s young winemakers on lovely castle grounds.

Still, the frequently blazing blue sky and curious tinny tinkle of church chimes, combined with the swearing of a harsh fisherwoman by the waterfront, and the chance to circumnavigate this pleasant petit ville on foot past water vistas make visiting Bourg well worthwhile.

The inclined and one-way main street, with tea shops, wine stores, a boucherie and several closed boulangeries (bakeries) is both attractive and somehow sad, a reminder of an era when there were more prosperous locals, and fewer indigents on the dole (au chômage) littering local cafes. During the past two centuries the population of Bourg plummeted by one third. Somehow, this town makes me lonely. Yet, friends who moved here from Australia or Bordeaux city tell of gregarious locals making them feel welcome, and of their appreciating quietness and calming vistas.

Several pedestrian and driving conduits link Bourg’s upper town and its lower port—stone channels, chutes and staircases. This town is a historical gem. But it is the hinterland of Bourg more than the city, the swelling hills and steeples and lost roads and sprawling vineyards and wine producers across miles of this ancient locale that give not only grace but economic agricultural abundance to this region.

I stopped at the winemakers’ crêperie restaurant near the water, avoiding the larger chain restaurant slightly uphill (a garish concoction of electronic menus and TV screens, food that appears to have been defrosted via microwave and staff who, at best, are disinterested). It was 11.43 a.m. The crêperie owners, a couple biding time on their porch, told me, after inquiry, that they would open at noon—‘midi’—and obviously cared not a fig about possibly seating me earlier to offer a pre-lunch aperitif.

Across the street I peeked inside a refurbished restaurant with a menu that included roasted goat cheese salad, moules (mussels) and dessert. I sat, ordered a glass of white wine from Château Mercier and food. Splendid.

After lunch I moved toward Blaye along the lower shoreline routes, Pain de Sucre (sugarloaf) followed by the Corniche de la Gironde. Here cute stone homes are separated from waterside gardens, transected by an old and thin rolling road. A woman in a rainbow red dress set glasses and cutlery on a garden table for lunch in proximity to where summer apartments—gîtes—are rented. Further ahead and behind the vines of Château Tayac, a stone roadside porch overlooks the estuary waters toward Bec d’Ambès, the point where the Garonne and Dordogne rivers merge and mate to form their mightier offspring, the Gironde Estuary, which flows north to the Atlantic Ocean. On this tongue of land, unfortunately, rest an ugly set of refinery tanks that should to be relocated.

This is close to where I live in the city of Blaye. I used to drive here and go running because the energy of open space and waterside vineyards and the confluence of rivers always churns out optimism and upwelling, a countryside certainty that just as seasons follow each other and plants bud once again after winter, life will continue regardless of financial or emotional worries, and irrespective of whether we hunt for certainty in a universe where that is elusive and slippery at best, and likely nonexistent.

Next, I passed the glinting church of Bayon—a gorgeous cluster of sandstone shapes: block, cylinder, column. Originally built in the 12th century and again a few centuries ago, the structure is a visual beacon of form and finesse, conspicuously seen from across vineyards.

Again, a thought arrived: what is a confluence but birth? A reminder that parents die and then only offspring exist. Just as rivers merge and parents mate, both produce downstream, or future, manifestations, whether estuary or child. And an estuary eventually flows into the ocean—itself a broad and almost boundless recipient of every confluence on earth, a possible metaphor for afterlife where the outpourings of every terrestrial river on this planet coalesce and mingle and one day evaporate to precipitate and transform, again, to some new and gurgling stream.

Along the corniche run gleaming sandstone houses with painted pastel shutters on a band, a belt, a strip of human habitation between estuary waters and nearby cliffs. This is a breezy land where residents tend to tend gardens, take walks in local hills and sometimes ride small skiffs in the flowing estuary.

My heavy (remember: bulletproof) silver Mercedes passed through villages and locations with gendered names: (masculine) Le Rigalet, (feminine) La Mayanne and sexless Marmisson. Here water splashed over reed covered rocks and a few marine engines throttled and I passed the still masted, though rusted withering shipwreck of the Frisco—scuttled in August of 1944 two days before Bordeaux was liberated from German occupation. During the war, these waters were riddled with mines to prevent invasion of of occupied Bordeaux city.

This journey takes place through both the ‘left bank’ and ‘right bank’ of the Gironde Estuary. Basically, left means west, and right means east, while the Gironde Estuary originates from two tributary upstream rivers mentioned earlier—Dordogne to the east and Garonne to the south (and, eventually, also east).

But what is an ‘estuary?’

It’s basically where a river meets the ocean, a combination of freshwater—from rivers—and saltwater—pushed upstream by oceanic tides. The constant smashing of river and tide churns up the water bed, spewing out nutrients on which marine life thrives.

The Gironde is the largest estuary in Europe, and the impact of salty tides is felt 100 miles (160 kilometers) upriver from the Atlantic Ocean. The estuary, by definition, runs from the mouth of the river at the Atlantic southward to the Bec d’Ambes (remember? Dotted with petrochemical storage tanks), the point where the Garonne and Dordogne meet.

This estuary is 47 miles (75 kilometers) long and 7.5 miles (12.5 kilometers) at its widest point. When you consider its total area, the waters of the Gironde at any moment form a region larger in area than Malta or Barbados, Guam or Andorra, or the Isle of Man and pour a quarter million gallons (one million liters) of freshwater into the Atlantic Ocean every second.

Twenty thousand years ago, when much of Europe was coated in ice, the ocean was hundreds of feet lower and this river valley held a mere trickle. But the climate warmed (gosh, without even fossil fuels or highways), waters rose and because Bordeaux city needed defending, forts such as Bourg and Blaye were crafted by stonemasons on limestone cliffs.

The Gironde has been a navigation and trade route since the Bronze Age, when copper flowed in from Spain, tin from Cornwall, and—later—wheat and flour were exported to Rome. From Spain came ham and olives and from northern Europe leather, wool, meat and dried fish, all gleefully traded for hogsheads of wine. But the wedding in 1152 of Eleanor of Aquitaine and Henri Plantagenet, future King of England, drove a boom in trade as wine began flowing to England with accelerated gusto. True, it stopped flowing for awhile after the 1453 Battle of Castillon (which ended the 100 Years War), after which the French booted the English out.

The lands around these waters buzz with life. Today the estuary’s marshy environment is a place of cattle herons, white storks, black kites and coots. Here are threatened pond turtles, as well as deer and wild boar. These waters run below a migratory axis for 130 birds species who alight to feed and mate and rest.

Blaye

Blaye, a city of some 4,000 residents is where I live. It has gained recent popularity, although was historically always strategic, being an estuary crossing as well as located along the route of commerce flowing from the interior of France and Bordeaux City (via the Garonne River) to the Atlantic seaboard as well as the world. It’s also a wine haven (both Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, while visiting Bordeaux, visited Blaye by boat) and a strategic military point (every king of France, except one, has visited).

Between 1685 and 1689, Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban—engineer, architect and author—oversaw the construction of the Citadelle of Blaye, a defense fortification that incorporates earlier forts and castles from as far back as the eight-century into its design. Built on 94 acres (38 hectares) that incorporated a village, this handsome lithic defense perches on a cliff above the estuary. It was a garrison for soldiers as well as a strategic canon perch (along with Fort Médoc on the opposite bank, and Fort Pate, on an island in the estuary) to thwart potential invasions of Bordeaux city to the south. The entire complex is now a UNESCO heritage site. Today it includes stores and restaurants, and holds fairs related to gardening, antiques, classic cars and wine.

Blaye (pronounced blYE), a town exposed to tides, is itself tidal with rhythms of change—whether quiet dark months of winter interspersed with bright summery crowds flooding to the international horse jumping days in July, or restaurants closing and being replaced, or the September grape harvest, a pinnacle moment, being matched by the equally buoyant wine tastings of April. There are tides of population movements: visitors, moving residents, cruise ship tourists gaping in shock at seeing lampreys and eels and horse meat for sale at the market.

There are free concerts on Sundays in August within the Citadelle, before magnificent views of the estuary—packed with faces both never seen and familiar. French is the rooted language in Blaye and to live here, you need some facility with that tongue, which means you actually need to grow roots to be a part of the fabric, the cultural warp and weft, of this locale.

What was once a significant medieval garrison (Blaye comes from Blavia, meaning the ‘Road to War’) as well as a hub of commerce now relies economically on wine production, jobs at the up-estuary electricity power station and tourism.

It’s easy to be at ease here. Within minutes from the front door I can stroll to the post office, bank, dry cleaners, boulangerie, fromagerie (cheese store), fruit shop, newsagents, bookstore, barber, coffee store, wine store and a half dozen restaurants. The vast inner open space and parkland of the Citadelle are a seven minute walk away and within three minutes I can step onto a ferry to the Médoc or wheel a bicycle onto a path leading eight miles (14 kilometers) northward through vines.

From the Citadelle, the view of the mile long Estuary and its islands Paté and Patiras is uncluttered and inspirational. This estuary, according to a local artist, is ‘the Mississippi Of France,’ and the right bank (here) includes amazing wine values. Which is why I’m publishing this little travel story on my blog instead of on Forbes: I don’t want anonymous hoards to show up and start unpacking.

There are ample festivals throughout the year for food and music and wine. Youth adore the annual Black Bass Festival, though fortunately it’s not held in Blaye, but somewhere out in the bush. If you play one song on stage there, you’ll acquire serious cred and likely be guaranteed a bevvy of groupies for life. I’ve never gone, never will. Not my scene. This year the listed bands include Hangman’s Chair, Psychotic Monks, Swedish Death Candy, Cannibale and I am Stramgram. Not exactly my playlist. But, hey, enjoy.

Here are moonrises and views of the estuary, inexpensive delicious wines, local seafood that sells for a fraction of most city prices, ample festivals and sound and resonant country roads to travel on by bicycle or vehicle or motorbike and enjoy peace, quietude, cafes with shots of espresso along fecund, burgeoning, lively and blossoming acres of fertile countryside. Here you live, love, spare a moment to reflect on life, starlight, long meals and ample camaraderie over a bottle of Etalon Rouge or Peybonhomme Les Tours wines to keep your soul ticking, satiated, insulated from mainstream politics and juiced up with the sight of phases of the moon.

If I could bottle and sell this experience, I’d make enough to retire here.

Thanks for checking in. Recent Forbes articles include pieces about Ruchè grapes in Piedmont, Italy, social entrepreneurs gathering at Windsor Castle and a lively new book about cocktails.

Lynn

21 Aug 2018Fantastic loop with great tid-bits of info. I’m bookmarking this to do with a friend this fall or in the spring. Look forward to #2 and 3!

vinoexpressions

21 Aug 2018Great Lynn! Let us know when you are around and we’ll introduce you to winemakers locally. You will enjoy!

Socrates A

24 Sep 2018Reading this brought back good memories having visited Bourg & Blaye from our river cruise trip that started in Bordeaux on Bastille Day 2 years ago!

With my spouse Olivia retiring next week:) we are hoping to come back & do a slow drive by of the area soon, so this article hit the spot! Thanks:)

vinoexpressions

2 Oct 2018Sounds good! Lovely part of the world here. And the temperatures now – September and October – are superb.