[This is the second of a three part series about a recent short journey. Part I is here, and Part III will come out next week. French words are italicized; some, not all, are translated.]

PART TWO: NORTH AND WEST.

It’s preferable to travel by train or bus or on foot if you are writing about travel. A car, obviously, needs to be driven. You can’t write while driving. You need to pull over. So, I often endlessly search for rest areas or alleys to pull into to capture notes and thoughts. All of this searching can suck away part of the joy of freewheeling and being on the road. Or else you can remember what you want to write about by constructing mental images—mnemonics (think of the book Moonwalking with Einstein). Years ago I once met and shared beers with a canoeist in Atchison, Kansas along the Missouri River. I had no recorder or notebook so configured his story mentally using a pyramid of interconnected images, then later transcribed our conversation, virtually verbatim, into a chapter.

The bizarre part was that he had worked overseas in Guam with land titles for 20 years, left his job, returned to the U.S., bought a canoe and launched into the upper Missouri River to paddle south before learning that the river had dams. Several. Each of them massive. Much of his expected river adventure turned into a series of lake water paddles.

Back to France:

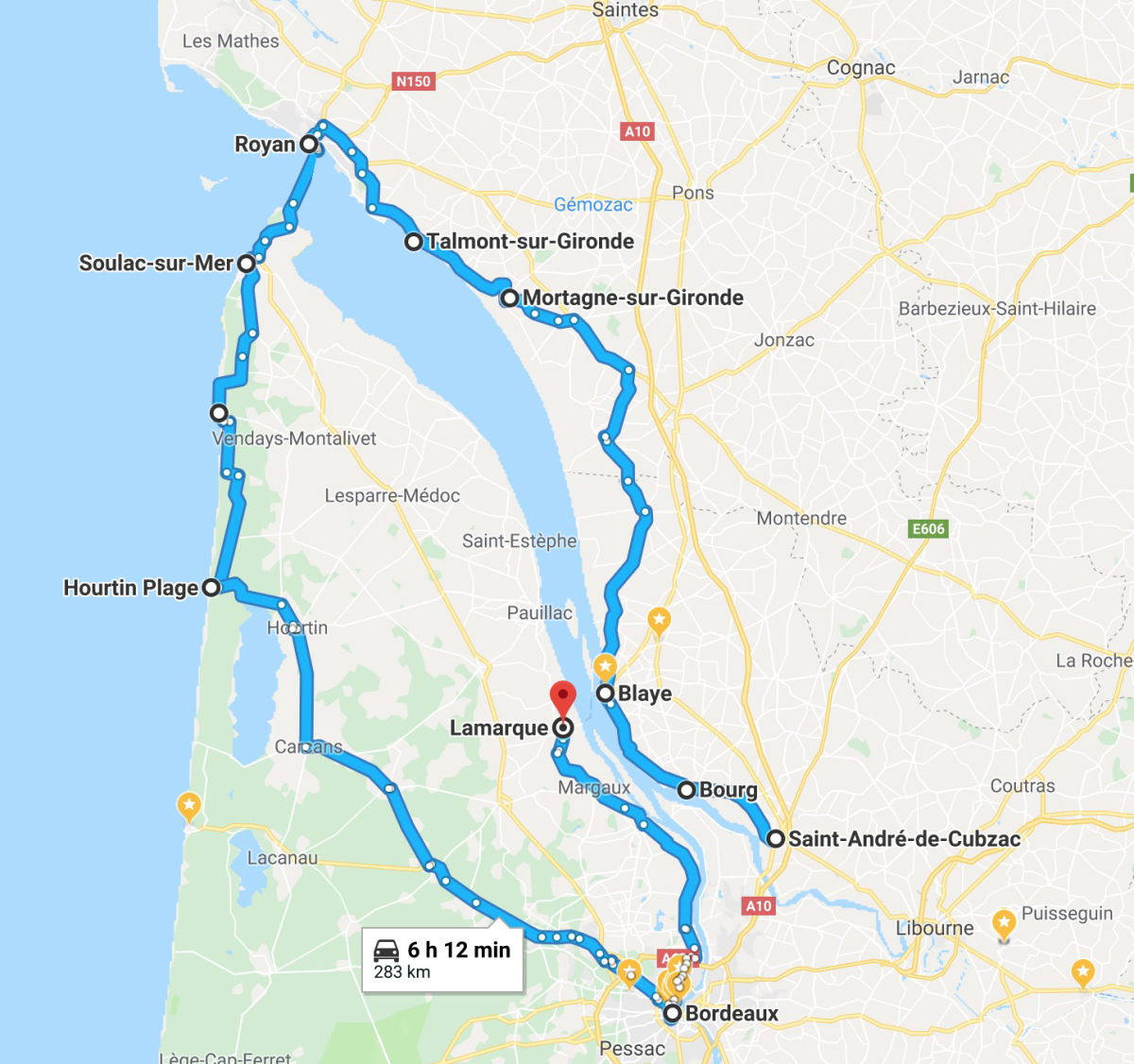

Regardless of the challenges of driving and writing, I continued on from the town of Blaye in southwest France, moving north.

I exited Blaye on an Ektachrome blue morning past the handsome slate spire of Château Lagrange and country roads with full, flourishing greenery and thick hedgerows. Around a country corner I passed Château Segonzac (near the final landing point for Operation Frankton canoeists during World War Two; more about that next week) across the street from a field of sunflowers.

Here were reeds, plains, spires, fields filled with stubble and dirt clods, and cyclists moving along thin roads bordered by wild earthen canals. Along the Route du Marais and Route de Montalpin beside Canal de Ceinture, I saw—miles ahead—four white cylinders, like salt shakers from a cheap diner, marking the local nuclear power plant—the Centrale Nucléaire du Blayais. Located on a plain east of the estuary, this assemblage of four pressurized reactors comprises the local cathedral of energy.

It’s been humming along since 1981, churning out thousands of megawatts and employing three hundred locals full-time. It produces a scant five percent of French energy needs and is poised across the estuary from Bordeaux’s Médoc, bastion of some of the world’s most renowned and expensive wines. One nuclear catastrophe there and, well, your precious bottle of Lafite might quintuple in value in the space of an earthquake. Is that possible? Who knows? Flooding in 1999 breached the walls and soaked the plant with 3.2 million gallons of floodwaters, while seismic shudders in 2002 threatened the integrity of its pipelines.

Next, through the town of Braud-et-Saint-Louis, gateway to the nuclear compound, and except for a roundabout and an eerily placed set of emergency warning klaxons on the roof of the mayor’s office, I saw little else. Visiting the power plant is off-limits except during special visitor days, so I moved past this thunderclap of power en route to Mortagne-sur-Gironde.

Miles up the road I stopped at Saint-Ciers-sur-Gironde, a bustling hive and cluster of Tuesday morning errand runners. At the Super U I bought a two chausson aux pommes and a mango passion fruit smoothie for breakfast. In the check out before me stood a woman with two girls—likely 5 to 7 years old—with their new school notebooks and markers and, bizarrely, a paperback copy of The Disappearance of Josef Mengele by Olivier Guez. Light reading, not.

I next drove through a happy slab of slanted vineyards and open views and entered the province of Charente-Maritime and within yards saw the first field of corn. There were doves and cooing pigeons and semi trucks hauling hay bales in this twisted, hilly, little known patch of geography that sizzles with quiet landscape beauty. I then navigated through thin roads in towns such as Petit Niort and lively Mirambeau, with its purple window shutters and rows of thick eucalyptus trees.

Mortagne-sur-Gironde

There is an upper and lower portion to the town of Mortagne-sur-Gironde, the upper being a long row of sand colored stone buildings, the lower being a port, perpendicular to the massive Gironde Estuary, with dozens of boats and a few waterside restaurants. During the same December flood of 1999 that gnashed at the nuclear power plant near Blaye, the tempest ruined a polder at Mortagne, a 470 acre (190 hectare) crop of diked and reclaimed land. It was never fully reclaimed.

The port is lively on a summer afternoon. I parked and walked past grassy spaces next to wooden gated locks, campers with fold out canopies and garishly colored lawn chairs, children dancing under trees, zones of poor internet service and a bikinied bicyclist taking selfies along a stone harbor wall. The Gironde is about a mile, or a kilometer and a half away, but the beauty of limestone bluffs meeting a silty delta next to prim and tended grassy parks with shaded benches makes this port attractive. A menu outside a linen table clothed restaurant gastronomique showed it was selling buffalo mozzarella gazpacho as well as duck cannelloni with herbs, but I decided to wait until the next town before lunch.

Talmont-sur-Gironde

Miles to the north, the view from the town of Chenac-Saint-Seurin-d’Uzet toward the town of Talmont-sur-Gironde shows a visually alluring angled slab of bright white sea cliff (likely limestone). This land includes cylindrical hay bales and mixed agriculture—dirty small sheep north of Mortagne, sunflowers, vines and muscular and cream-colored cattle chomping grass with fury.

In Talmont-sur-Gironde I sat in shade on a restaurant porch and ordered merlu (hake) fish and a Leffe beer, followed by an apple tart—tarte aux pommes—slathered with caramel covered ice cream.

Whereas Mortagne is shaggy, Talmont is prim. Parking at Mortagne is free, but costs in Talmont. Campers and bikers and locals flock to Mortagne, while urban families and couples with convertibles trundle into Talmont. On busy summer days, Mortagne is a fiesta, while Talmont is a zoo. In Mortagne, lunch lasts an unrushed two to three hours, while in Talmont, four separate servers on a crowded patio cater to every need, as though in the U.S.,and whoosh out dessert before you even switch from drinking an entry beer to a glass of dry white wine. In Mortagne, the restaurant staff speak French; in Talmont they practice English, whether or not you like it. Mortagne is France; Talmont is California. And if both were in California, one would be Ventura, the other Newport Beach.

‘Now, coffee and bill,’ a server said loudly in English as he plopped both on the table before I’d begun downing the glass of wine. His action was polished, though slightly rude and harried.

Still, walking after lunch was golden. Views within and from little Talmont are splendid—mud flats and fluttering birds and tidal waters all somewhat reminiscent, on a minuscule scale, of Mont Saint Michel in northern France. Here there is wind, a balustrade of climatic temperance that mitigated an otherwise harshly hot week. This wind becomes a song in the ears—rustling reeds, licking tree branches, scudding cumulus and vibrating its bounty of peace. Clean air and clear vistas from the shores of Talmont: magnificent.

Estuary waters look muddy from here, though the sight of snow white egrets and the laugh of cycling couples is, in the wake of wine and beer and a seafood at lunch, sumptuous. Truth is, I love Talmont.

It’s a wee promontory around Saint Radegonde church, originally constructed in 1094, a time when Saint Marks Basilica was consecrated in Venice and just before work began on the Cathedral of Durham in northern England. The church and village jut into tidal waters and are riddled with cobbled alleys and little stores. I love its stony white paths, elevated trail above water and sight of seabirds on seaweed coated isles; the brazen blocky église, the photogenetically trim vistas and the myriad of colors on rock and soil and cobbles. There is a Venetian profusion of little alleys here (again, on a minuscule scale) leading to who knows where.

Bicyclists of all ilk gather here, whether healthy and not, compelled by a shoreline visit that blends brutal history with skittish and deft scenes of nature. So, more power to both venues—Mortagne and Talmont, although I’d hate to see the ritual of a lazy two wine bottle lunch supplanted by Anglo Saxon infatuation with speed, table turnover, efficiency, profit and time.

This is also home to Les Hauts de Talmont wine, which produces biodynamic wines, including a 100% Colombard white, as well as a red and a rosé made from Merlot. Co-owner Jean-Jacques Vallée told me the story about these wines when we met.

I left town but soon pulled over and parked in a park within the nearby villages of Arces-sur-Gironde because the church is a beauty, and I marched through a ghostly silent village, relishing birdsong interspersed with silence.

Back in the car I listened to Gregorian music while passing slanted fields of sunflowers—tournesols—their heads pointed downward to avoid August sun in this land of escargot and pineau fortified wine and estuary sturgeon caviar and the summer clank and rumble of rubber tractor wheels and grinding motors.

Royan

The next morning I woke to rain and soon dialed the car radio to a channel named musique (which was classique) and by 5.20 a.m. heat pushed into the car, forcing me to crack open windows. The scent and whoosh of nature zipped in and, combined with the beauty of outer fog sheets, felt uplifting.

I passed the lovely small beaches of Meschers and the long open sands of Saint-Georges-de-Didonne and moved into the cloying whiff of highway diesel outside the city of Royan. Many buildings in this city of 18,000 residents are concrete and rectangular and painted white with navy blue porch rails. Streets curl along with seaside topography and are generally wide and lined generously with trees. It’s a cross between some 1960’s Floridian beach architecture and that of a modern coastal California suburb. Strategically located at the northwest entry point to the Gironde estuary (largest in Europe), the city was 80 percent leveled by bombs during the Second World War, so the absence of medieval charm is understood. Parts of the city have a positive and prosperous vibe, with BMW sports cars sweeping out from occasional gated communities to secure family morning lattes.

A wooden walkway and a parallel stone bicycle path curl around the beach periphery lined with profusions of planted flowers. The waterfront here is a maintained and orderly, with an air of respect for health and fitness. At 7.00 a.m. both a gardener and a leaf blower were humming with industriousness.

I stepped into dawn light and the salty, invigorating scent of ocean air, then shivered in a cold 60 degree breeze while wearing shorts, sandals and a thin shirt. I sat on a park bench at an ocean point on Boulevard de la Côte d’Argent—reminded by its ocean freshness of California’s Laguna Beach or Ireland’s Salthill. (Another reminder of Laguna Beach: a conspicuous sign notifying that from April 1 to September 30th, no dogs are allowed on the beach.) A tractor was grooming the cove’s sand beside Casino Barrière and red-roofed waterside stone homes across this little bay—Plage de Pontaillac—appeared attractive and cozy. The memory of having packed a warm sweater in the car was welcome.

At 7.08 a.m., men in their 60’s were going swimming (freezing!) or bicycling and a 30 some year old woman, all togged out in sports wear and strapped with some electronic health monitor, went for a very slow stroll. The breakfast porch of four-story and three Star Hotel Miramar looked inviting, but I whiffed the scent of fresh croissants from down the street and hunted the source on foot, still shivering.

At pâtisserie-boulangerie Chocolat’in, on Rue de la Plage, I bought a roll filled with chocolate chips, then sat on another bench near seagulls and strollers. I eyed the northwest elevated edge of the cove with its two dozen painted white wooden fishing shacks. Here be palm trees, joggers and slow rolling waves during the easy morning transition to dawn.

I soon meandered along a park profuse with geraniums and roses. This square—Mado Maurin—includes a curling bike path near a pizzeria. Standing youths wearing suede jackets finished their breakfast pastries and then, in bare feet, push started a friend’s Fiat near the Surf Club Royan. I was underdressed but excited about the up coming ferry ride across the yawning mouth of Europe’s largest estuary. The car ferry, known as le bac in France, next departed next at 9.00. I paid at the entry booth, parked next to vehicles with snoozing vacationers, then went for a walk.

Anchored close to the Captainerie building bobbed tugs and massive catamarans, sleek yachts, rubber dinghies with heavy engines and sailed fishing boats.

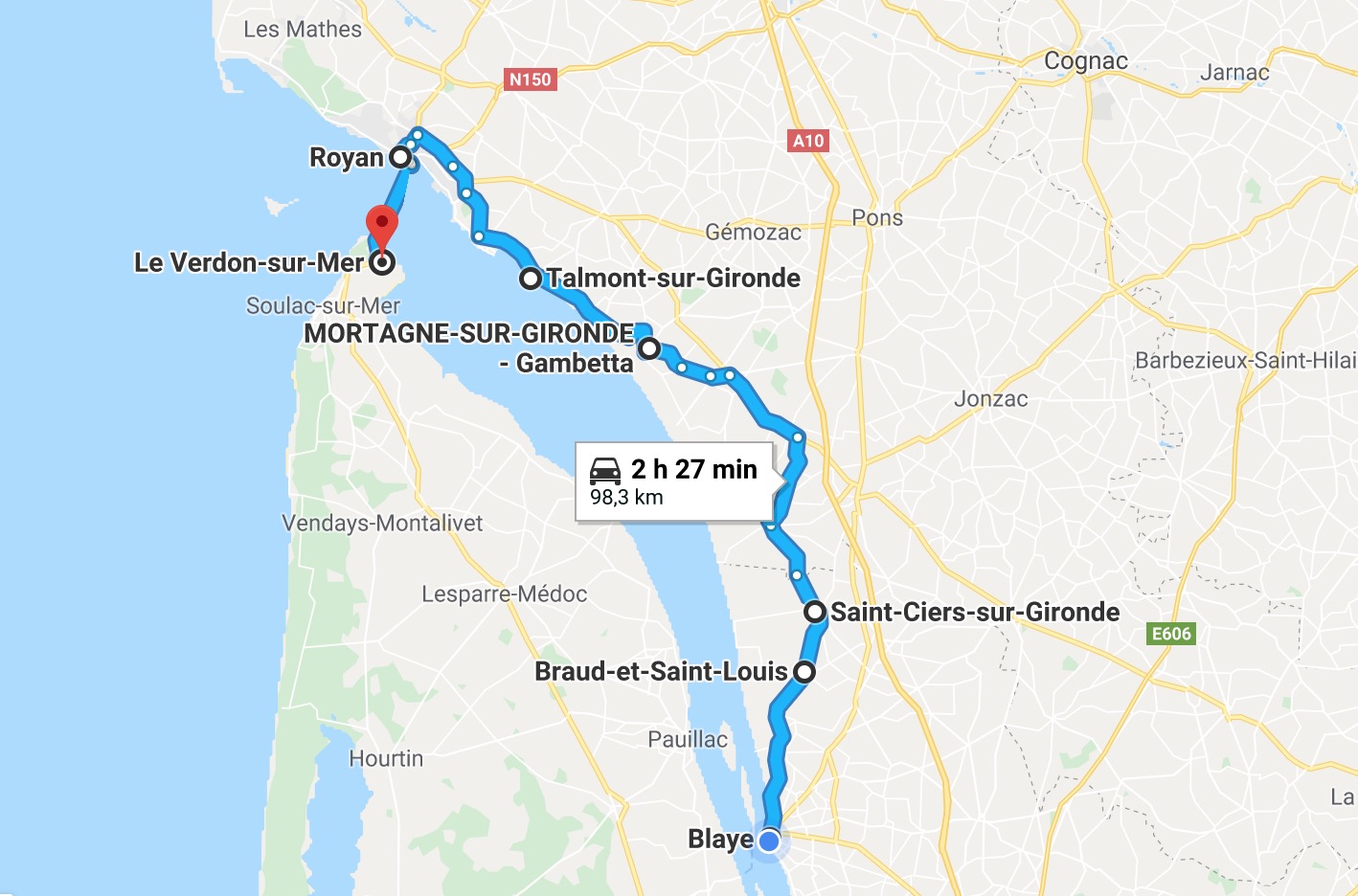

I wondered why this northern ferry cost 50 percent more than the ferry between Blaye and Lamarque further south. After departure, I realized that it is, in comparison, an asphalt highway compared to a dirt track, a Marriott versus some Motel 6. You pay at a booth from your car window before even entering the dock space, are assigned a waiting line, and eventually drive straight on to park. Simple. No ejecting passengers who have to walk aboard on foot, no maneuvering 180 degrees before being barked at to reverse into a narrow back slot and then having to stand in a line to pay. The indoor waiting room of this northern ferry includes not just a coffee machine, as in Blaye, but a cafe staffed by two selling an ample range of drinks and snacks.

Northern Médoc

The ferry departed at 9.00 to a massive horn blast, then aimed at the far shore with its sloping green grassy sand dunes, a point of natural beauty. Westward and within the ocean stands the towering white Phare de Cordouan lighthouse, oldest in operation in France. It was first built by the Black Prince Edward of Wales in the 1360’s, about the time the bubonic plague ended, the Chinese Ming dynasty began, the 100 Years War raged, Pope Urban V tried moving the Papacy back to Rome from Avignon, Muscovites built a Kremlin Wall around their city to oppose Lithuanian invasions and the Thai Kingdom conquered (once again) Cambodia.

Waves on this crossing are oceanic, not estuarine: whopping great swells that lurch stomachs and shift stances only minutes after departure. The bac pivots up down and sideways—like a traveling fairground ride—impacting platoons of passengers: capped grandpas, cuddling lovers and families munching baguettes. After twenty minutes it threaded a needle between concrete pillars and entered the modern harbor at Pointe de Grave. Vehicles and dozens of bicycles disembarked, including families and a lean bronze muscled couple paddling tandem with backpacks.

I soon stopped across from LeClerc supermarket Le Verdon-sur-Mer and walked across the street to Epicerie Chez Cathy—small and stocked with fruit and veg. There I bought a peach from a prim and polite young lady and outside saw a beautiful roadside counter of fish on ice garnished with greens. Two energetic women at this mobile poissonnerie—Bateau Cassy—sell maigres, bars, dorades, and soles, all festooned with slices of lemon. Both businesses—Cathy and Cassy add a local market dimension to the looming adjacent chain store.

Next, south to Soulac-sur-Mer, and then onto Bordeaux City.