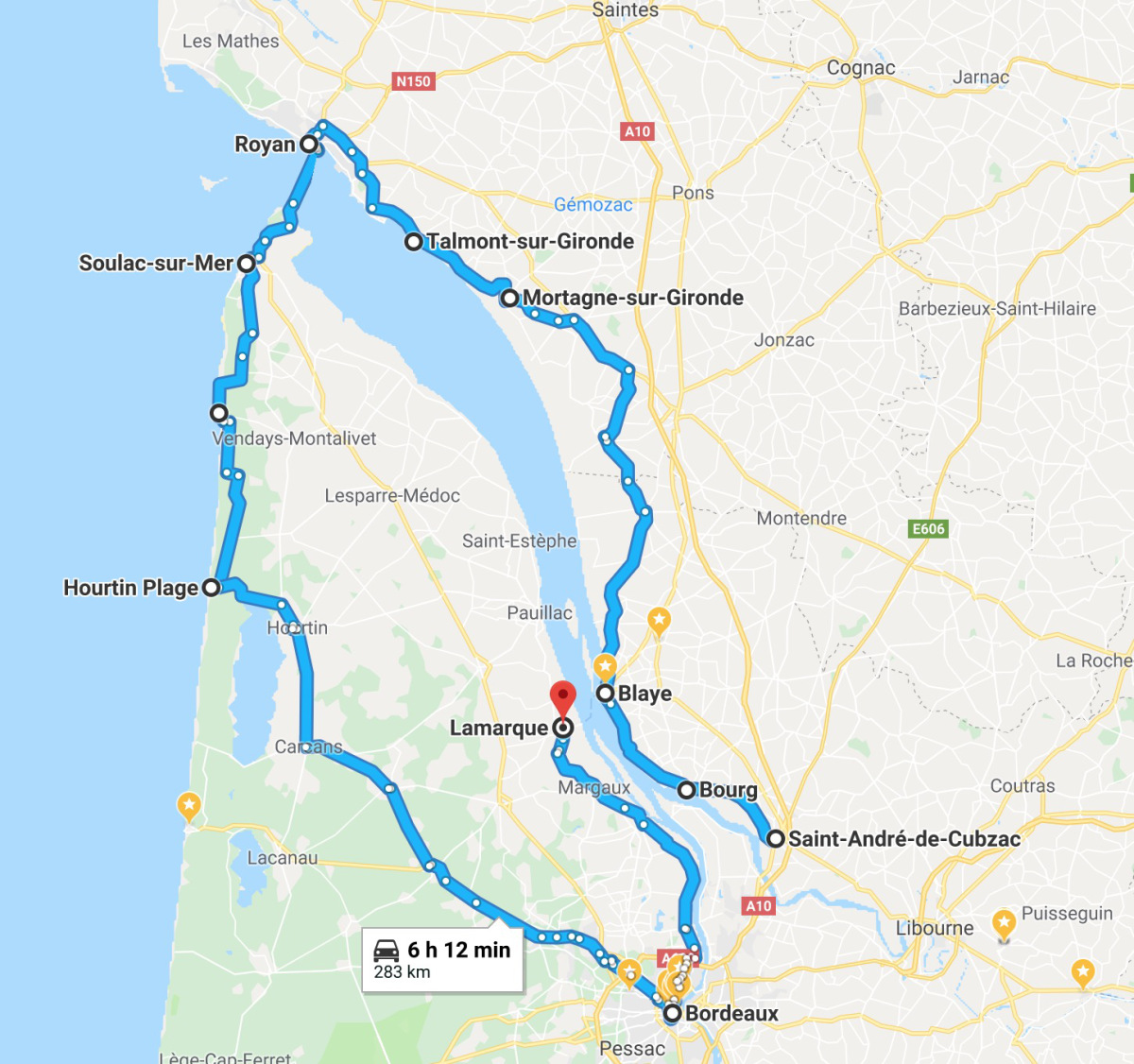

[This is the last of a three part series about a recent journey. French words are italicized; some, not all, are translated.]

This post is a few weeks overdue…

PART THREE: FOREST, SHORES, CITY

Soulac-sur-Mers

I pulled off a sweater, rolled up sleeves and began the 3.5 mile drive to Soulac-sur-Mer.

The roadside included pine and palm trees, sandy road shoulders and villas behind trimmed hedges, white wood fences or chains linked by squat brick columns. This made the locale appear to be a similar but slightly shaggier version of famed Cap Ferret further south. One bonus here: ample parking.

Near the Atlantic Ocean I found a museum run by the Memorial of Fortresses in North Medoc. Part of France was occupied by German forces during the Second World War, including the country’s coastal western strip. Resistance was organized and coordinated (including by the British) both in England and surreptitiously in France.

Inside I looked at old uniforms and guns and photos and maps in glass cases. There were hand grenades and medals and rusted pistols and drab olive green gas masks as well as buttons and belt buckles. Everything was aged and oxidized and most had been dug out of local salty sand. The curator at this little outpost sat me down before a small television screen that showed a black and white video of war footage in France. It was all people prancing with victory music and aerial shots of bombarded ships and capped French officers hoisting flags as American tanks squeezed along dirt roads. The black and white footage included medals pinned on soldiers, salutes, handshakes, marching in formation and roadside crowds cheering on French troops. If only victory had been that clean. The museum is a reminder of how heavily fortified and defended this peninsula was by Germans, as well as of bloody battles required to recapture this terrain.

One war story is that of Operation Frankton, where a group of 10 soldiers, led by the initiator of the plan—Herbert ‘Blondie’ Hasler—paddled five canvas canoes (each with two-persons) from the mouth of the Gironde Estuary to Bordeaux city, placed mines under German ships and then retreated to a northeastern estuary bank near Blaye before escaping on foot.

The operation was akin to the Doolittle Raid of Tokyo in 1942, when 16 U.S. aircraft bombed that city. The real damage was not physical but psychological—alerting enemies to unrealized vulnerabilities in the heart of their best defended positions.

Only four of these soldiers made it to Bordeaux to inflict minimal damage and only two—Hassler and canoe partner Bill Sparks—escaped. Two canoes, swamped by ocean waves, immediately vanished at the mouth of the estuary, and another six men were apprehended and executed. After the war Hasler organized, and participated in, a single-handed transatlantic ocean race between New York and Plymouth.

Outside I spied a blazing trio of flags—American, French and European. I pulled over to where dunes rose and waves roared. Here was a bronze miniature Statue of Liberty. Rescued from abandoned disuse in Paris in 1980, the statue now celebrates the Marquis Lafayette, who at 19 years of age departed France in 1777 to fight for liberty in America, then returned to France to participate in the Revolution. The statue was made from original molds used to model the actual Statue of Liberty.

A father walked his two young daughters, each three feet tall and wearing a turquoise bicycle helmets as well as mirrored sunglasses with colored frames. He carried their bicycles across the street into town. If not for victory, I wondered, what freedom would those children have now?

I kicked off sandals and climbed dunes, toes squishing through delicious layers of warm and cool sand, and looked westward across waves, ever attractive and always inspiring. Soon I visited another beachside memorial that included four French flags and names, hundreds, inscribed on a black marble wall commemorating the 1944-1945 liberation of Point de Graves, this northernmost tip of the Médoc.

Soulac-sur-Mer is a regular beachside holiday town, stuffed with roadside parked cars and a waterfront with dozens of international flags. Along walkways and the main road moved morning joggers, a stylish young brunette in a polished black Mini, a stroller carrying a scared terrier in his arms and ample men with ugly, unkempt and unwashed Rastafarian braided dreadlock hairstyles—each moving arm in arm with a female mate, each resembling a runway model. Did I recently miss the onset of this bizarre latest trend?

At noon, I ordered an orange juice at Les Chiens Fous. From an outer table I watched a healthy parade of multicolored generations reveling in the wind bitten and sun soaked day, evincing joy and health and movement and some sensible disregard for social media for at least a few hours.

Soulac’s summer highlights include ample bicycling, family friendly everything, juicy fresh fruits and historical reminders of a darkly jagged history where liberty eventually prevailed over an industry of genocide. Times have changed, people have moved on, nations and identities have—thankfully—merged.

On the southern edge of the city I found a shack of a wine store. A glazed eyed man in a cap with a remote and faraway look melted into his lawn chair out front. I walked in.

A rotund and chummy woman appeared. We spoke. They sold two types of wine. One from Perpignan, on the other side of France; one from Castillon on the other side of Bordeaux city—itself far away.

I inspected the Castillon. Five euros for a bottle of red. And the Perpignan. Three euros a bottle for rosé. That included the cost of shipping it across the country. I decided to buy both to try. If the rosé was a go, perhaps California’s Two Buck Chuck may have met its match. I pulled bottles from the counter. Later I tried the rosé. Not Bad. Not good. Not really a surprise.

Montalivet

The beach of Montalivet, further south along the Atlantic coast, parallels thick pine forests and dunes demarcated by a long and shaggy wood picket fence. Here again there was bicycling for all ages, surfing, kite surfing, beach volleyball and beach soccer. The town’s abbreviation in ‘Monta,’ hence signs for Monta Surf School and Monta Pizza.

Pedestrian Avenue de L’Ocean was as jammed and sweaty as a summer outdoor concert. There were bikers in black bandannas, a skirted boy wearing a pearl necklace and a swarthy, bearded chap in a pirate’s hat. I counted 24 people in line outside the ATM. This crowded summer family scene with too many bodies hungering for fast food made me return to the car and get out…fast.

The southern outskirts of Montalivet skirts several forests: Dunaire, Vendays and Junda. There are adjacent miles of bicycle trails, as well as a separate asphalt bicycle path paralleling the road through deep, dense, lovely woods—all a glorious escape after the pedestrian human zoo of Montalivet. Long distance bikers (many with children) moved with loaded panniers, while shirtless boys skateboarded. One couple picked roadside blackberries. The towering, expansive woods of the Médoc are a cathedral, a living and breathing respite from nearby sea tides of humans clustered on narrow streets. Although this road is a patchwork of asphalt repairs—a buckled, neglected semi-artery through the woods—it magnificently lacks bleating crowds.

Hourtin-Plage

I liked Hourtin-Plage immediately: a square grassy park, uncluttered side streets, dispersed groups of people with nothing to prove. I sat at a shaded table at Le Grillon Restaurant and ordered fresh tuna with herbal vinaigrette sauce and Château Pouyannne white wine from Graves—poured into a less than pretentious big bulb of a glass with the words Gallo Family Vineyards printed on the side. Then, aha! Once again: seated dead ahead—another lame knot of ugly and unwashed dreadlocks on an enervated youth eating lunch together with a ten star babe. What is going on, World?

Rated restaurants hope to neutralize unpredictability by providing consistently good food. Sometimes this works; not always. There’s strange, unpredictable magic in dining out. Michelin Star restaurants offer food that is visual artwork, although not always delicious, and staff can be as stilted as furniture in a doll’s house. Better to have good people, soul filling and reasonably priced fare that is delicious as well as decent wine (even table wine) with friendly staff who treat diners alike whether they are celebrities or off duty dishwashers. You can’t predict when you’ll find this confluence. This restaurant ticked those boxes, and was a pleasure to visit. The atmosphere was quiet and happy, and the staff unrushed but efficient.

For dessert I ordered a café gourmand (you don’t know what this is? It can change your life) before motoring south to Bordeaux city.

Bordeaux City

This has been a cracked and brutal summer with tree leaves, burnt and withering, turning yellow and brown mid August. August is an odd and mobile month in France, a time when train stations may close on Friday mornings (for whatever reason), when libraries often close for the month and school-free students with weird haircuts loiter and slouch and share lame jokes at train stations or on street corners. This is traveling season when commuters haul luggage more often than shopping bags and vines look trim and grapes full and dangling.

The Garonne River looked gloriously muddy, its shores a pastel of muck and weeds while beyond rose beautiful Bordeaux city spires and stately architecture, all as deliciously proportioned as a well decorated Christmas tree.

Spires in this city welcome you, a reminder that this was home of Eleanor of Aquitaine and centuries of medieval knights and troubadours, sword and ax fights and wandering bards. The spires piercing skylines are part of lithic architecture that curls parallel to, and along, the city’s winding waterfront.

I parked near the main railway station, Gare Saint-Jean, which is as much destination as thoroughfare. Here classical piano music rang out and the overall vibe was less raucous than stations at, say, Paris Montparnasse or Milano Centrale.

Out front were trams and a bendy bus departing for Place de la Bourse (5 stops). I boarded and paid. Away it whooshed and rattled along past road construction near Pont de Pierre, the stone bridge crossing the Garonne with 17 arches, one for each letter of Napoléon Bonaparte’s name.

Near the water of River Garonne is Bourse, a wall of beautiful stone apartments and offices. Across the street is a sizable horizontal fountain with multiple jets that spray mist or flood the surface with water a half inch deep. Kids lay down and did snow angels and belly rolls and everything that makes parents cringe at seeing their children wallow on stone earth before a battery of strangers. Still, kids here are generally not bratty or loud or obstinate but whisper and sing and cuddle their parents with overt affection.

A tour guide who looked pre-teen carried a red flag on a stick and marched a group of visitors across Place de la Bourse, She was followed by a sizable woman and several youths attired with the latest style of backpack—basically pear shaped leather pouches on strings slung so low that they bounce off wearers’ rear ends.

Others drove rental bicycles over square cobbles, jouncing butts and boobs and halting to take toothy selfies. They’re all very stylish these French: couples with matching sailor shirts and a woman in debonair silver lace sandals pulling a chique but heavy chunk of luggage across cobblestones. This contrasted sharply to the attire I saw weeks earlier in the aisles of Walmart in rural New Mexico.

I moved by foot into the sunny heart of this magnificent city, compact and clique, global yet quintessentially French. Here is a smattering of public squares—places—that makes the city infectiously attractive: I begin at Place de Parlement with woofing dogs, two lost cyclists, a three year old holding her mother’s bouquet of flowers and roadside stone bollards linked by thick and weathered chains. I passed a parked pink Vespa near to where diners scarfed down plates of salad nicoise and drank golden ales and light yellow wines.

Then, up Rue du Pas-Saint-Georges with its abundant little eateries—terraced and table clothed—such as Le Saint Georges and Osteria Da Luigi. Next—past Place Camille-Jullian with an ancient Roman column and performing tightrope walker and trimly dressed ambling Asians who smelt of lavender.

For a light dinner I ate at an Asian restaurant across from Bradley’s Bookshop (‘Coffee & Tea Taste Better with a Good Book!’). This is the confluence of Rue Saint-Siméon, Rue de La Merci and Rue Arnaud Miqueu.

Earlier in the bookstore I had purchased a Jared Diamond book The World Until Yesterday as well as Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari and three short stories by Nabokov and then walked outside and relished the gorgeous temperature. There on Rue Saint Siméon clunky dented bicycles were chained in twos, like drunken sentries, on metal rails and I noticed several American visitors dressed alike: sneakers, beige cargo shorts, gray t-shirts.

There I dined outside—à l’extérieur—and ordered Saké Teriyaki and a half bottle of Château Boyrein white wine from Graves and wallowed in the acoustic beauty of young French ladies chatting at the adjacent table. The dress and comportment of families and couples here was sleek and trim and bereft of loudness or bulk.

Eating with chopsticks, I noticed the constants of summertime: mirrored sunglasses, tanned legs, older wrinkled French wives sucking on vapes, short sleeves showing off intricate tattoos. Most families, even when herded on crowded streets, stayed harmonious and polite.

Even in the most hectored and aggravated cobbled intersections, stuffed with ambling bodies and toddling toddlers I was amazed to see driving school vehicles shunting along these rues (one came close to taking out the entire table of gabbing teens beside me).

If not full on savoir-faire on the part of visitors who obviously just arrived, they displayed a quiescent hush, as though in a cathedral during service. This toning down of loud voices showed respect for a location different from their home.

It is easy to love this city, including its understated power (three times it functioned as the alternative capital of France) and its yawning confidence—much like a Grand Cru Classe wine that commands a committed audience and generates a fat bank balance. A thousand years ago the Aquitaine was the veritable living Elysian Fields of Europe.

Without being reputed so, this city is also a pillar of style and fashion and architectural glory (dusted off by Mayor Alain Juppé, who led the cleaning of stone buildings since his election in 2006).

Next, up the main shopping street—pedestrian Rue Sainte-Catherine—which, near its northern (theater) end, is slightly inclined and heaved with swarms of pulsating humans, sweeping their own divergent paths, clutching plastic bags and bicycle helmets and with clicking heels navigating baby strollers and parading tattooed thighs or signal-red lipstick as they cooed and froed and peddled scooters or paraded along this artery, this aorta, of an ancient yet revitalized city. Tanned sisters bantered about lingerie before Yves Rochet while necklaced divas darted into H&M, and a snoozing, horizontal indigent—his cap and framed family photo propped up on the walkway before him—actually made money while he slept.

I diverted westward off Saint-Catherine along Rue de la Porte Dijeaux. At first the stone road was inclined in a steep V for drainage and had a whiff of urine but I sallied forth past the stores: Galeries Lafayette and L’Atelier du Chocolat (try a feuilleté blanc or Rocher Suisse Noir—sinfully delicious) and passed young ladies gandering at summer dresses in the window of Bimba y Lola.

This street / rue then intersected with Rue Vital-Carles, which offered an inclined gape at the rosary window and graceful spire of Cathédrale Saint-André. Here, a tram car passed—not the blocky stocky style like those from Lisbon but sleek and blue and whispering efficiently along rails tastefully embedded in stone pavement.

Here at the corner is Librairie Mollat—a book selling institution in the city with its blue tinged wooden window frames showing abundant titles (Varuna by Charles Frazier, The Burning Chambers by Kate Mosse and A Column of Fire by Ken Follet).

Then, on foot through the ancient stone gate—Porte Dijeux, built in the 1700’s to commemorate the ancient western, Roman entrance to the city. Outside Le Bistro de la Porte drinkers at round marble tables languished with books and parfaits and eerie green cocktails while loud jazz throbbed through a cheery humid Friday afternoon.

I spotted second hand books for sale, including one on how to be a perfect gentleman—Le Guide du Parfait Gentleman—with a chapter titled comment être sexuelle (how to be sexual).

Place Jean Moulin gave a flurry of brazen impressions—gesticulating visitors wearing Hawaiian shirts and girls rolling cigarettes and every person in this open space belittled by the ancient, shiny, imposing spire of Saint-André cathedral.

Next, down Cours Pasteur—eerily empty at 4.51 on a Friday afternoon, past a bicycle store selling bangers and a vapid ‘international bar’ that can’t even attract locals. I sauntered through Place de la Victoire with its live Peruvian flute music, an Egyptian obelisk and a magnificent old stone Román door beside a sinuous street. I hiked along at a rare clip in order to drive northward to catch the ferry back to Blaye.

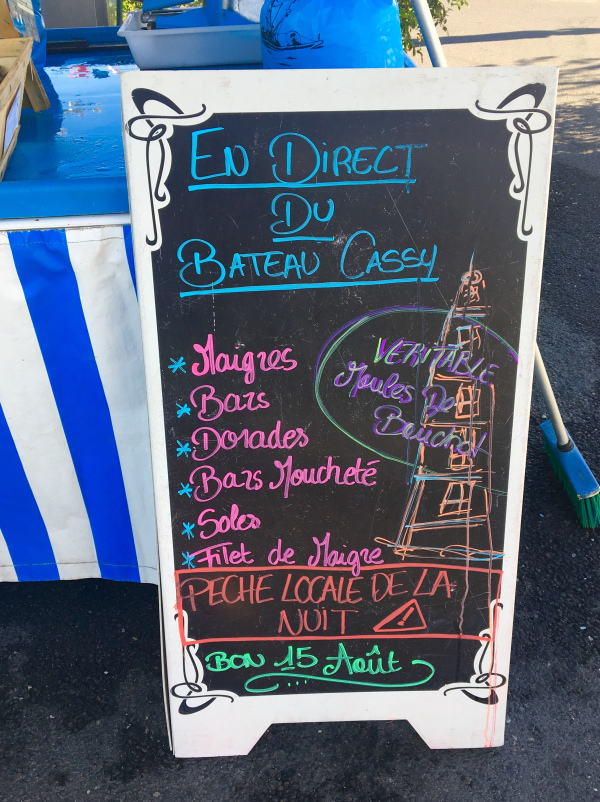

Then along Cours de la Marne past Marché des Capucins where strange spices, bizarre fish and esoteric vegetables flourish in cool interior stalls during weekends. From Bordeaux city I drove northward, through the famed wine country of Médoc (which I’ll omit, having covered it in so many other stories and articles).

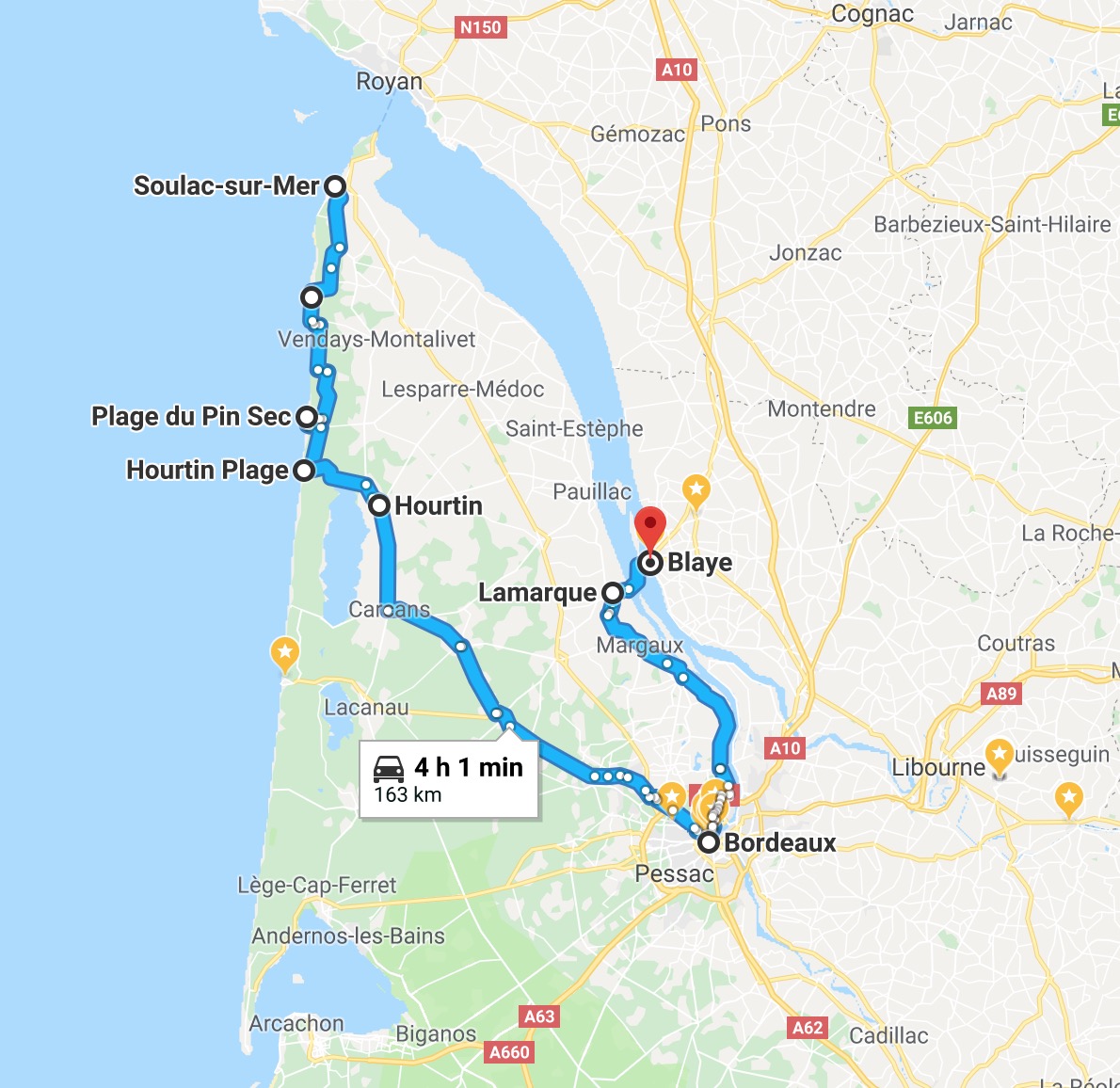

The Ferry Home

The road northward to Lamarque ran along groomed and clean roads passing well snipped hedges and grassy but mowed road shoulders. The church spire of Lamarque resembles a long bullet, or the capsule cover to a syringe.

Finally, homeward on the Lamarque to Blaye car ferry. The 3.45 p.m. boat left on time, pirouetted in sun dappled but muddy water and the day, with fresh breezes on that Friday afternoon in August was uplifting and, considering it marked the completion of this local driving loop—perfect.

During the 25 minute ride to Blaye I sat upstairs in sunshine where the sight of the nearing cliffside Citadelle looked beautiful. Perfect. Like home anywhere.

^ ^ ^

Thanks for tuning in again.

My latest Forbes pieces are here, and include sparkling wine from Trentino in Italy, why it’s worth visiting the beaches of Bordeaux, and a slice of Bali in Bordeaux.