People buy famous and expensive wine brands for different reasons.

One reason is that they can be a decent investment—which is valid.

Another, somewhat unsettling, reason relates to risk aversion.

An essay in a recently published Wired Magazine outlines this logic*. According to Rory Sullivan, vice-chairman of the New York marketing firm Ogilvy & Mather Group, one reason people buy renowned brands is that humans instinctively want to avoid disaster, rather than seek perfection. Famous brands may not provide perfection, he notes, but their reputation means that they will likely steer you clear of disaster. They are, he wrote, “…an exceedingly reliable way of avoiding buying something which is awful.”

Unless you are purchasing expensive and renowned Bordeaux First Growths to lay away in a cellar to sell later, or hang out with deep pocketed friends, or are trying to impress somewhat shallow visitors, is it worth shelling out serious cash for wine? Some say yes. For me, there are a few mind-altering Burgundy wines for which I might fork over $100 per bottle (and certainly not frequently). But thousands, or tens of thousands of dollars to buy less than a liter of fermented grape juice?

Why?

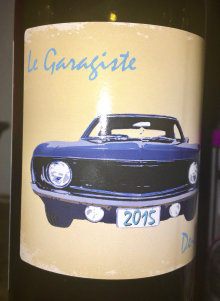

I’ve sampled a few pricey Grand Cru wines. A few (certainly not all) are mediocre. For daily drinking, I’d be more inclined to nip down the road to any of a dozen local châteaux selling splendid wines for south of 20 Euros a pop (including the 8 Euro La Garagiste made by a wild-haired Brit named Ben—good stuff).

I’ve sampled a few pricey Grand Cru wines. A few (certainly not all) are mediocre. For daily drinking, I’d be more inclined to nip down the road to any of a dozen local châteaux selling splendid wines for south of 20 Euros a pop (including the 8 Euro La Garagiste made by a wild-haired Brit named Ben—good stuff).

If you want to buy more expensive brands, fine. Just don’t be confident that the level of wine quality will raise commensurately with the price.

This short video highlights problems concerning price and quality.

Or, you could ask a critic.

Famously expensive brands, after all, attract ‘experts’ and ‘renowned’ critics.

Perhaps some ‘experts’ hope that this association with an established tide of renown may somehow float their own levels of self-esteem, public profile, or even income.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with that. Human nature, at times, causes us to be attracted to that which is popular.

But some ‘experts’ may soon become disposable.

Here’s why.

In his highly readable, fascinating and excellent book titled Thinking, Fast and Slow—Nobel Prize winning author Daniel Kahneman tells the true story of a Princeton economist and wine lover named Orley Ashenfelter. In the 1980’s this man, who publishes the Liquid Assets newsletter, thought it would be worthwhile to predict the future value of Bordeaux wines based on the weather in the years when the grapes grew. Generally, wet springs impact the quantity of wine produced, while warm dry summers can be wonderful for quality.

Ashenfelter designed a mathematical model with an input of just three weather-related factors:

- The average temperature over the summer growing season.

- The amount of rain at harvest time.

- The total rainfall during the previous winter.

Using this, he could predict average wine prices not only years ahead, but decades into the future, with a correlation between his predictions and actual prices of 0.90.**

Pretty dang good.

He predicted 1986 would be an average vintage, vying against the prediction of world renowned wine guru Robert Parker.

Ashenfelter was correct, not Parker.

His impetus for creating this mathematical model came from observations of a wine château owner in the St. Estephe region on Bordeaux’s left bank. Ashenfelter’s algorithm worked so well that it had the potential of rendering opinions of ‘experts’ obsolete.

So—they trashed it.

When this happy mathematician paraded his algorithm (an example of ‘demystification of expertise,’ as Kahneman called it) within prominent wine circles, the reactions—according to a New York Times article—ranged between ‘violent and hysterical.’ The Wine Spectator magazine stopped letting Ashenfelter advertise, while Robert Parker called his research ‘ludicrous and absurd.’

Not everyone was skeptical. One Yale professor suggested that if others were not told these predictions derived from mathematics, more ‘experts’ might be willing to accept them. But, no.

“The prejudice against algorithms,” Kahneman remarked in telling the tale, “…is magnified when the decisions are consequential.”

And popular input regarding the price of expensive wine? Very consequential.

[What does it take to become a wine critic? This Irish brewer found that it’s not difficult to judge wines, as long as all are relatively awful.]

But seriously, the conclusion?

- Consider why you want to purchase an expensive wine with a renowned brand name.

- Perhaps an algorithm can help you select wines of better value.

Regarding number 2, learning about Ashenfelter’s research only a few weeks ago struck an inner bell.

Two years ago I developed an algorithm—to identify the best value wines within any specific wine region. It combines two factors—one being subjective, which is taste, the other being objective, which is price. Like Ashenfelter, in developing it I used a regression analysis to calibrate the model. The mathematics are not linear because, when humans hit a sweet spot as far as quality goes, they are more receptive to opening wallets and purses to fork out more greenies for that lovely liquid.

The reaction I got for this mathematical model? It ranged between fascination and wariness. The most gifted wine taster I ever met (a young French man) was polite, though suspiciously inquisitive. Generally, however, its merit still waits to be proved.

Spring has arrived here in Bordeaux. That means it will soon be time to take out this Vino Value algorithm again for a road trip or two, combining quality with price to recommend the best value wines to purchase. Previous uses focused on wines from California’s Anderson Valley, on the Finger Lakes wine region of New York as well as on the Loire Valley and on wines from the Cahors region.

I’ll keep you posted as this model rolls out again.

In the meantime—remember the point of the above stories: be confident in your own judgment of which wines you like, and be wary of buying any wine just because it has a ‘label’ that equates with expense.

Prices aside, here are a few insights into what constitutes quality in wine.

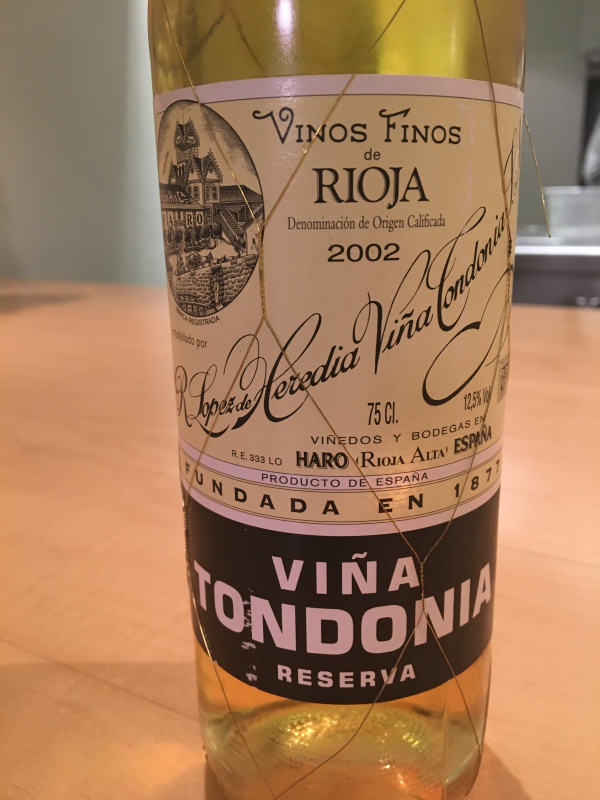

Finally, my latest Forbes articles are here, including a recent piece about why you will seen an increase in new blends of Rioja white wines.

Coming attractions include….

…the Dordogne region of France. Thanks for tuning in.

And a final question:

[polldaddy poll=9697195]

Notes:

* See The Wired World In 2017 – ‘In The Game Of Life, Anything Times Zero Must Still Be Zero.’

** Kahneman suggested that one reason for the inferiority of ‘expert’ opinions is that “…humans are incorrigibly inconsistent in making summary judgments of complex information.” He continued by writing, “The research suggests a surprising conclusion: to maximize predictive accuracy, final decisions should be left to formulas, especially in low-validity environments.” (Those are domains with a significant degree of unpredictability and uncertainty, which applies to the quality of wine and the vagaries of weather.)

Comment below if you like.