Médoc means middle territory, appropriate for the French wedge of land seated between Atlantic Ocean waters on the west, and the Gironde Estuary to the east.

Pine trees grow on the ocean side of this land strip, while swamps and vineyards sprawl eastward. The soil is crappy. It’s so poor ‘you couldn’t even grow potatoes here,’ our energetic guide, Matthew, told us. But vines that struggle through nasty soils often produce excellent wines. Combine that truth with the underlying complex limestone substrate, ocean winds deflected by a massive pine forest, well-drained gravel soils, seasoned winemakers, the best French oak barriques, and the particular soup of all natural elements on the Médoc – the terroir – and the resulting ‘left bank Bordeaux’ wines are some of the most prestigious, and expensive, in the world.

For renowned wines, there are the usual suspects: three châteaux classified in 1855 as Premier Crus (Lafite, Latour, Margaux; the fourth, Haut-Brion, is located south of Médoc, within Bordeaux city) and another added in 1973 – Mouton Rothschild.

Yet the beautiful Médoc is electrified by contradictions. It is traditional yet anachronistic, conservative but liberal, pure and still polluted. The strict, ancient laws of viticulture and wine production adhered to locally are admirable: irrigation is illegal, wines must be produced from grapes grown on châteaux properties – not imported, and for red wines to be labeled ‘Bordeaux,’ they must include a blend from at least two, but no more than six, specific grape varietals. (Whites, making up only eleven percent of Bordeaux’s wine production, usually include three varietals, although a total of nine are allowed.)

That’s tradition.

But the ranking of which châteaux produce the best wines is an anachronism. Four of the five top Bordeaux Premier Crus were ranked highest by Thomas Jefferson during his visit in 1787, and re-ranked the same by the French in 1855. This accepted classification system has not changed since, with one exception: the addition of Mouton Rothschild in 1973, in a dodgy act of political legerdemain.

To agree on the utter validity of this century-and-a-half old ranking system is a compliment to Thomas Jefferson as well to Emperor Napoleon lll. Otherwise, it is nonsensical. Soils change depending on how they are cared for, as well as due to effects of erosion; climates shift to favor slightly different patches of land over time; excellent winemakers may be replaced by mediocre, and winemaking techniques have improved dramatically during the past two decades, much less century. The dogmatic adherence to an ancient classification system flies in the face of logic, natural resource economics, and science. Yet regardless of discussion over the history of the classification system, the entire region of the Médoc as a whole retains a valid reputation for producing excellent red wines.

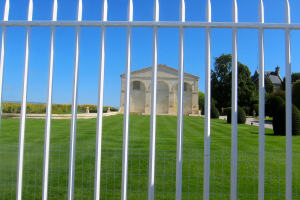

There is also the conservative versus liberal slants on wine production. Chateau Pontet-Canet, a stone’s lob from Premier Cru Mouton Rothschild, was classified in 1855 not as a first, but as a far lower fifth grow. Yet it now produces wines that sell for a fraction of those from neighboring Premier Cru lands, and are often ranked as highly. Wine Spectator Magazine rated the 2005 Mouton slightly lower than the Pontet-Canet, yet it sells for over $500 a bottle, while you can get a bottle of the Pontet for about a hundred bucks. And while the 2009 Mouton may rank a tad higher than the 2009 Pontet, a bottle will cost you two to three times as much as the Pontet.

Pontet is also now embarking on some vineyard techniques that might appear liberal within the local context, certainly in a universe separate from most of their Médoc brethren.

To understand this is to grasp an agricultural perception of the difference between pure versus polluted. Some soils of the Médoc have been nuked with fertilizer and pesticides for decades. The result? No one is quite sure what soup of trace chemicals they’re quaffing down with each sip of their beloved Bordeaux. Whereas most of these stately châteaux selling bottles for the price of small diamond brooches utilize traditional fertilizer and pesticides, others forge ahead with more ecologically sustainable ways of keeping their soils healthy. Pontet-Canet is now certified as a biodynamic wine producer. Considering that it is located in the heart of the traditional wine-producing country of Médoc, that’s like hanging a Jackson Pollack painting next to a Monet at the Louvre – certain to raise eyebrows.

But whether or not you subscribe to all biodynamic practices – be they planting and harvesting by lunar cycles or spraying nettle teas on your crops – biodynamic methods are fundamentally healthy for soils, and promote the notion of working in concert with natural cycles, rather than trying to dominate them. The practice encourages bugs to return to abandoned soils to burrow and aerate the land. Pontet-Canet is also moving toward using horses rather than tractors to work the soil – resulting in less compaction and erosion.

The results? Taste to find out. You won’t be disappointed.

Please take a rapid survey to help improve this site. This will help me to provide you with more of what you want. Thanks.