Last spring I spent time rambling through the Languedoc and Bordeaux regions of southern France. The brief video below includes not only shots of vineyards (conspicuously absent of greenery), but three structural highlights visited during the trip – the Canal du Midi, Carcassonne Fortress, and the Citadelle of Blaye.

All three relate to the curious history of wine production in France.

First, check out the video.

Both the Languedoc and Bordeaux are massive wine producing regions. Bordeaux has long been associated with high quality wines, while the Languedoc was historically renowned for mass produced table wines. No longer. Cellar magicians in the Languedoc are now focused on quality and character, and some excellent, meticulously crafted wines from that region are available at a decent price. (Check out a previous post about the Languedoc.) In my book Vino Voices, Charles Capbern-Gasqueton gives a tasting of Languedoc wines from the French AOC (appellation d’origine contrôlée) regions of Corbières, Minervois, Berlou, Cessenon, and Faugères. An excerpt is included in a previous blog post.

(Charles, a wine and barrel dealer from a Cognac producing family, told me: “You need people to say, ‘This wine, I’m sorry but even if it’s from a famous château, it’s just crap.’ It’s like food. Tonight you’ll get a piece of meat from the butcher. It’s beautiful meat. You go to the supermarket, and it’s going to be crap….Wine is to be a real pleasure. It needs to be fun, exciting, simple. Now they make so much fuss about wine it’s pretentious, snobbish, and boring. You need to be with a real winemaker, you don’t want beautiful girls with small skirts showing you around…”)

Incidentally, the Guardian newspaper recently included a good article on Languedoc wine.

Now, back to those structures, and a bit of history.

Canal du Midi –

Construction of the 150 mile long Canal du Midi was completed in 1681, joining the southeast coast of France and the city of Toulouse. Because Toulouse was already connected to Bordeaux (on the eastern coastline) via the Garonne River, the canal provided the missing link for a sea-to-sea waterway passage from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic.

Building the canal was what one non-fiction author (of a most excellent book, by the way) deemed a feat of ‘impossible engineering.’ The notion was not only technically challenging (no water projects of any great scope had been constructed in the region since the Roman Empire), but psychologically daunting. Local farmers were baffled by the notion that humans were brazen enough to try to alter the course of nature, and were equally stupefied that it was financed by the seat of the government (which they generally held in suspicion) in northern France.

The notion of the canal had lasted for centuries. Leonardo da Vinci even visited France to scope out the prospect for building such a canal. The visionary who piloted the actual scheme, however, was a retired tax collector named Pierre-Paul Riquet who assuaged the fears of locals, then garnered local confidence and support to plunge ahead with the work. Unexpectedly, the most technically oppressive challenges of hydraulic engineering were partially solved by laboring women who had descended from their farm fields in the Pyrenees mountains to pick up seasonal work. Back home, they and their ancestors had spent centuries maintaining and modifying Roman built irrigation networks. From this, they possessed an almost innate knack for helping to size, shape, and arrange the layout of locks and water routes, as well as to understand the subtle behavior of gravity flowing liquid – a gift to project engineers who lacked such hands-on experience or knowledge.

Once the canal was constructed, all sorts of wares – including wine – flowed in both directions. This led to the Bordelaise implementing taxes and regulations to keep Languedoc wine from encroaching on their own wine export business. However it also provided an avenue for Bordeaux wines to more easily reach Italy and other neighboring regions, so others could taste for themselves whether all the international hype they had heard about French wine had merit. (This export had been going on for long: pottery fragments in Italy’s ancient city of Pompeii, destroyed by a volcanic eruption in AD 79, include writings that indicate the wine came from the region now known as Bordeaux.)

Carcassonne

The massive fortress of Carcassonne began as a simple mound fort established by Romans, and grew through multiple iterations over centuries. It was invaded by Visigoths, defended (eventually) against Saracens, sieged by crusaders – always maintaining inland poise as a stopping point along the old Roman route that linked the Mediterranean to the Atlantic – established long before the Canal du Midi existed. It’s likely to have housed its share of wine traders making the coast to coast trek centuries ago, though any wine transported that distance would likely have been affordable only by the wealthy or by royalty. Sure, swarms of visitors visit Carcassonne. But if you are ever in the region, choose early morning (preferably) off-season to visit, and enjoy much of the inspiration it provides in peace. It’s worth it.

Citadelle of Blaye

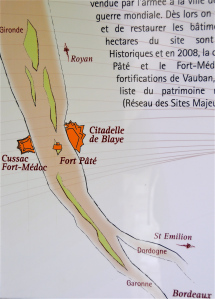

Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban was a military engineer and adviser to King Louis XIV who constructed massive defensive complexes within France in the 1600’s and early 1700’s. One of these was the Citadelle du Blaye (now a UNESCO World Heritage site) on the eastern bank of the Gironde estuary that bisects Bordeaux.

The Citadelle provided national defense, and also vigilance against pirates intent on looting ships laden with wine which regularly sailed to Britain for trade (the wine trade between Bordeaux and England has thrived at least since the 12th century).

These structures were constructed without the aid of internal combustion engines or electricity. They were built using animal and human labor during ages when Novocaine and antibiotics were unavailable. Whenever someone tells me they would like to have lived during a past era, I think – no thanks. The romance of that notion is great, but the reality would have been a hard slog.

Chrissie

8 May 2014Tom, sounds like a great trip to a beautiful part of the world (not that I’m biased!) Love the description of ‘cellar magicians’ in the Languedoc, so apt. To me, this is one of the most exciting wine regions in Europe. And pretty easy on the eye;)

vinoexpressions

9 May 2014Lots of open space there, Chrissie…the wine can be hit or miss, but the number of ‘hits’ appears to be growing with time. Am missing France…and look forward to exploring more – including Rhone/Provence…your home territory!